By Rob Carrigan,

robcarrigan1@gmail.com

The Comanche were skilled horsemen operating in loose-knit bands that ranged through New Mexico, Southern Colorado, Oklahoma, Southern Kansas, Northern Texas and Northeastern Arizona. As a people, it is estimated that nearly 50,000 roamed the plains in the early 1800s. Most language experts think the word “Comanche” is a Spanish corruption of their Ute name, Kohmahts (those who are against us). The Sioux word ‘Padoucah’ was often used interchangeably by the early French traders for both Comanche and Plains Apache.

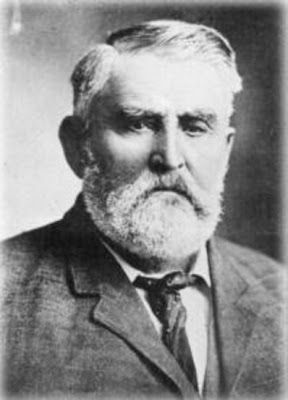

After riding 800 miles bareback when he was just nine years old in his family’s migration to Texas, an experience that left him permanently bowlegged, Charles Goodnight appeared destined to become a cowboy, renowned Indian fighter, and legendary trailblazer.

Brief stints as a horse jockey, mustang breaker, and freighter prepared him additionally. As a very young man, he and his half brother J. Wes Sheek, partnered to help a neighbor, and as a result of tending 430 cows, they received every fourth calf that dropped. By 1860, the two counted 180 head in their herd in the Keechi Valley of Texas.

The Civil War however was not far off on the horizon.

“Soon after moving to Keechi, Charlie met Oliver Loving, the most experienced cowman upon the northwestern fringe…” wrote J. Evetts Haley in his 1936 biography “Charles Goodnight – Cowman and Plainsman.”

“Loving was then running a small country store on the Belknap road. He owned a few slaves and good-sized herd of cattle, and, though Cross Timbers were not yet producing vast herds of beef, most of what were produced found a market through him. He usually trailed them to Shreveport, Alexandria, or New Orleans.”

In 1858, Loving trailed a herd to markets back in Illinois.

“Then the gold rush to Colorado began, and he learned that the Denver country was swarming with people.”

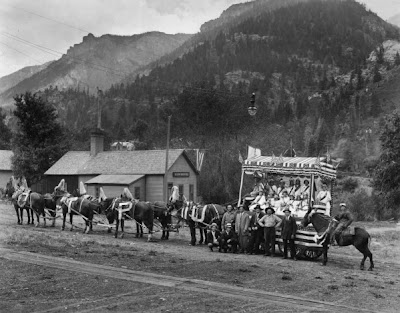

In August of 1860, Loving with his then partner, John Dawson, started out with a herd of 1,000 head for Colorado. Charlie helped them clear passed Cross Timbers to the Red River and they headed for Indian Nation. They reached the Arkansas River below the Great Bend and followed it up to Pueblo where they wintered the herd on the very grass where, ten years later, Charlie himself would establish a ranch.

“When spring came and melted the snows, Loving drifted into Denver and peddled his cattle out to miners and prospectors. Whole thus engaged, the Civil War broke out and the authorities refused to let him return to Texas. He had made friends with Kit Carson, Lucien Maxwell, and other prominent mountain men, and through their intercession, was allowed his freedom. He left his outfit, staged it to St. Joseph, and reached home on August 9, 1861, full of plans for Southern aggression. However, the destinies of war decreed that he should feed, rather than lead men who fought, and these plans were forgotten,” wrote Haley.

A few years prior, Texas had established Indian reserves that in theory, were designed to stem attacks from Comanche and Kiowa raiders in areas near the Brazos and Red Rivers.

Just before the Civil War broke out, Sam Houston, called out of retirement to serve as governor, recognized that Indian raiding on the Texas Frontier was as bad as it ever had been. He immediately called for Federal troops and supplies, dispatched Texas Rangers, and authorized organization of Minute Men in the border counties.

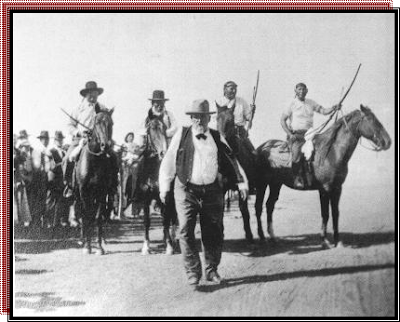

It was the Minute Men, and later with the Rangers, that Charlie Goodnight became an accomplished Indian fighter and scout of uncommon skill and knowledge.

In one particularly violent episode involving a chase and fight of Comanche raiders who had killed ranchers in the Pease Valley, Goodnight was present when Cynthia Ann Parker was ‘rescued’ by a combined group of Rangers and Minute Men. Parker had been abducted as a child and after Comanche raiders killed her parents, she lived among the Comanche for years. Quanna Parker, her son was notable historically as the last Comanche chief, and years later Goodnight would negotiate with him to end raiding in the Palo Duro area of Texas.

Goodnight describes the meeting of Ms. Parker in a letter later.

“The squaw was in terrible grief. Through sympathy for her, thinking her distress would be the same as that of our women under similar circumstances, I thought I would try to console her and make her understand that she would not be hurt. When I go near her I noticed that she had blue eyes and light hair, which had been cut short (symbolic among Comanche women as a sign of mourning). It was difficult to distinguish her blond features, as her face and hands were extremely dirty from handing so much meat.”

“After speaking a few words to her, I turned back the creek where there was great excitement over the fight, come in contact with Judge R.W. Pollard and told him we had captured a white woman. His reply was ‘No!’”

“Go see for yourself,” I said, wrote Goodnight in the letter.

“Cynthia Ann was sent to relatives in the piney region of Texas, where she was oppressed by strange terrain as well as crowded by strange people. No longer of the race of the hated Tejanos, she yearned for the treeless plains where Nocona and her sons still hunted the buffalo, and sinking in with grief and loneliness, she died, apparently of a broken heart, in 1864 – an expatriate among people of her own blood. Her tragic story is a part of the Texas tradition,” wrote Haley.

Because of his recognized skill at finding water, understanding Indian ways and providing advance knowledge of the plains, Goodnight became a trusted scout for the Texas Rangers satisfying his obligation to the Confederacy.

“Released in 1864, he returned to find his portion of the herd had grown to 5,000 head of roaming cattle. He and Sheek negotiated with Varner, bought the entire Varner herd, and by 1865, had 8,000 head,” wrote Mike Flanigan in a 1986 article for the Denver Post.

After the war, Longhorn cattle, like Goodnight’s, had roamed free and fattened like the Buffalo in central and south Texas. Those returning from the war looked to them as a livelihood by both legitimate and nefarious means.

But there wasn’t a local market.

“During the war, herds were driven east and south to Memphis and New Orleans to feed Confederate armies. But now the money was in the North. Thousands were trailed to St. Louis, Kansas City and Chicago to satisfy a growing appetite for beef. Later Abilene, Dodge City and other Kansas towns became target for Texas Cattle. With the need for stock on the northern ranges, cattle drives stretched to Colorado, Wyoming and Montana, and Goodnight herds were in the Vanguard,” wrote Ray Pomplun in a 1974 piece for the Denver Post.

“Lack of local markets led Goodnight to blaze cattle trails, but fearing the northern towns were flooded by other herds, he first looked west to the mining camps and Army installations in New Mexico and Colorado. The code for his cowboys was strict. He once trailed a herd three days alone after firing his help for violating rules. He trailed 10,000 cattle a season for nine years. Other drovers handled more but none branded the frontier with character and personality as did Charlie Goodnight.”

In 1866, after creating a new partnership with Oliver Loving, Goodnight, the two of them and 18 cowboys crossed the alkali desert east of the Pecos, and completed a drive deemed impossible by other cattlemen.

“The last 90 miles to the river they were parched by heat and no water, but Goodnight, with superior knowledge of Texas cattle, pushed his herd 72 hours without rest. Ten miles from Horsehead Crossing, the cattle smelled water. Goodnight pushed the strongest to the front, taking them to the river without losing a hoof. Then he returned to help Loving with those half dead from thirst. One hundred head drowned at Horsehead, later called “the graveyard of the cattleman’s hopes,” and 300 perished on the hot, dusty trail,” wrote Pomplum.

They sold most of the herd to the government and with the drive already a financial success, Loving trailed the rest on into Denver and sold them to a Colorado legend in his own right, John Wesley Iliff.

“Before the end of the cattle driving era, 300,000 head traveled this route, remembered as the Goodnight Trail, and quarter million more went on to Denver. The complete route west from Belknap to Fort Sumner, then north to Denver, is known as the Goodnight-Loving Trail.

Always there was a threat from the Comanche, and to some extent Arapahoe, along the trail.

“Years afterward, a trail outfit engaged in battle with Indian near present site of Roswell, so the story still runs, in which another cowboy was killed. He was buried beside the Goodnight Trail, and the cow-camp poet, deficient in Biblical allusion, arranged a couplet to be carved in sandstone so that all who passed might read that:

He was young, and brave, and fair.

But the Indians raised his hair.

It was the Comanche that eventually took Goodnight’s partner in the fall of 1867. Loving, impatient about bidding on government stock contracts in Santa Fe, convinced Goodnight that he needed to go on ahead. He and another longtime hand, “One-armed Bill Wilson” left but ran into serious Indian trouble when a band of about 100 raiders charged them near the Pecos. Loving’s wrist was shattered early in the fight by a rifle shot, and after locating a hole to hide in near the river, “One-armed Wilson” set out for help, swimming past watching Comanche on the river, walking barefoot through Cactus in desert for miles and days in his underwear.

“His eyes were wild and bloodshot, his feet were swollen beyond all reason, and every step he took left blood in the track,” wrote Goodnight later in letters about one-armed Wilson's discovery on the trail days later.

Regardless, after feeding him and provide additional clothing, Goodnight and several others set out immediately to try and save Loving. Wilson precise instructions guided them back to where he left the older gentleman, but he wasn’t there. The rescue party assumed he was a goner.

But he wasn’t.

“… For two days and nights he fought the Indian at bay while enduring the pangs of hunger and fever of his wounds. And when help did not come, he concluded the Indians had captured the herd and killed the hands, and he decided he must follow Wilson’s lead. Though the wound in his side had not proved serious, few could endure a shot-shattered three foodless days and sleepless nights without collapse, but in spite of his age, Loving was blessed with a constitution of iron. The Indians had continued to shower his positions with rocks, and tunneled through the dune to within a few feet of where he lay, but lacked the courage to break in upon him. On the third night he crawled into the water and started upstream, instead of down, hoping to reach the trail crossing about six mile above, where with good fortune, some passer by might lend him aid,” according to Goodnight’s account to Haley.

“At last he gained the crossing and lay down in the shade of a clump of wild china, only about four feet above the water. He attempted to shoot some birds that came into the trees, but the river had soaked his powder and caps and his guns were useless. He tried to eat his buckskin gloves, but could not kindle a fire to parch them to a crisp, and again he settled back to wait. For two days and nights he stayed there, too weak to move, but satisfying his thirst by tying his handkerchief to a stick and dipping it in the river below. On the third day his superb endurance broke and he sank into a stupor.”

He was found there by four boys and taken in to Fort Sumner by wagon. When Goodnight finally discovered Loving was still alive, he set out to make the long trip there. Gangrene had set in and his arm needed to be amputated but Loving didn’t want the operation performed until Goodnight arrived. The arm was removed but an artery proved troublesome. After 22 days following the amputation and relapse, Loving, sensing his time had come, summoned his partner the night before he died, and he asked Goodnight to preserve the partnership for two more years.

“The Confederate Government owed him a hundred and fifty thousand dollars for cattle he had delivered, which financially ruined him, and he asked me as a Mason to give my word to continue the partnership for at least two years, until his remaining debts were paid and his family provide for. I told him that while I was willing to do this, his oldest son, who would be executor of his will, knew me only as an illiterate cowboy, and would certainly object to my going on with the business,” said Goodnight in later interviews.

“I know that, but James does not know you, and I do. Ignore him. Your promise is all I want.” Goodnight gave him the promise and another. That he would return his body to Texas eventually. Loveing died September 25, 1867, and was temporarily buried at Sumner.

Several months later after finishing trailing the herd and establishing a ranch in southern Colorado, Goodnight returned to Fort Sumner, exhumed Loving’s body, and after a number of cowboys beat oil cans flat and soldered them together to make a huge tin casket. Haley described the process in his book.

“They placed the rough wooden one inside and, packed several inches of powdered charcoal around it, sealed the tin lid, and crated the whole in lumber. They lifted a wagon bed from its bolster and carefully loaded the casket in place. Upon February 8, 1868, with six big mules strung out in the harness, and the rough-hewn but tenderly sympathetic cowmen from Texas riding ahead and behind, the strangest and most touching funeral cavalcade in the history of the cow country took to the Goodnight and Loving Trail that led to Loving’s home.”

###