"Only Crazy Bob would be out here taking pics. Thank heavens he did!"

__ Tom Casper, on a Facebook post of one of Robert W. Richardson's photos.

Taking the last freight train to Dolores

By Rob Carrigan, robcarrigan1@gmail.com

It was sort of typical. Robert W. Richardson was out in a blizzard on the Rio Grand Southern railroad tracks taking a series of photos of the last freight train to Dolores on December 19, 1951. It didn't stop him from a few snaps of the work Goose and other things along the way. In fact, it encouraged him, and became a hallmark of his long and wonderful life.

Bob Richardson founded the Colorado Railroad Museum (also sometimes known as the Narrow Gauge Museum) in Alamosa, CO in 1941. There, he had a motel and several pieces of retired narrow gauge rolling stock that he showed to visitors. His collection eventually outrgrew the space in Alamosa, so in 1958 he partnered with Cornelius W. Hauck, who helped purchase the current property in Golden, where the Colorado Railroad Museum (CRRM) remains today. The CRRM officially opened to visitors in 1959. At that time, Bob had the Iron Horse Motel on the property, which was torn down around 1970 in favor of collecting more rolling stock and completing a loop of track on which to run trains.

"CRRM Co-founder Robert W. Richardson Dies at age 96"

Said the headline by Ron Hill, Colorado Railroad Museum, Photo by Mallory H. Ferrell

"Fondly

called “Uncle Robert” by all those who know and admired him, Robert

William Richardson, age 96, passed away peacefully in State College,

Pennsylvania, on February 23, 2007. Although plagued by short bouts of

illness in recent years, Bob had remained basically healthy and in full

possession of his remarkable memory and sharp wit right up until the

end. Perhaps best known as the co-founder and longtime Executive

Director of the Colorado Railroad Museum and a distinguished railroad

author and photographer, Bob’s career could easily have gone in a

different direction. Born in Rochester, Pennsylvania, on May 21, 1910,

he moved with his parents to Akron, Ohio, in 1915 and later graduated

from high school there. Diverted from a college education, Bob went to

work for a local hardware concern until the depression cost him his job.

Along the way he had learned the printing business and proceeded to

start his own small print shop in Akron. The depression years were

especially hard for printers, and Bob’s shop closed in 1937. Stamp

collecting was one of his major hobbies, and George Linn hired him as

the second editor of “Linn’s Weekly Stamp News,” the principal

publication dealing with that interest. Fortunately, for rail hobbyists

and historians, Bob’s other hobby was railroading," noted Hill in his obituary.

"Fondly

called “Uncle Robert” by all those who know and admired him, Robert

William Richardson, age 96, passed away peacefully in State College,

Pennsylvania, on February 23, 2007. Although plagued by short bouts of

illness in recent years, Bob had remained basically healthy and in full

possession of his remarkable memory and sharp wit right up until the

end. Perhaps best known as the co-founder and longtime Executive

Director of the Colorado Railroad Museum and a distinguished railroad

author and photographer, Bob’s career could easily have gone in a

different direction. Born in Rochester, Pennsylvania, on May 21, 1910,

he moved with his parents to Akron, Ohio, in 1915 and later graduated

from high school there. Diverted from a college education, Bob went to

work for a local hardware concern until the depression cost him his job.

Along the way he had learned the printing business and proceeded to

start his own small print shop in Akron. The depression years were

especially hard for printers, and Bob’s shop closed in 1937. Stamp

collecting was one of his major hobbies, and George Linn hired him as

the second editor of “Linn’s Weekly Stamp News,” the principal

publication dealing with that interest. Fortunately, for rail hobbyists

and historians, Bob’s other hobby was railroading," noted Hill in his obituary."As a teenager, Bob enjoyed watching and photographing trains in Ohio and Pennsylvania. His insatiable curiosity led him to study railroad operations and history, and later he wrote articles for both “Trains” and “Railroad” magazines. In anticipation of forthcoming military service, he quit his job with “Linn’s” but then learned that he would not be called up for some time. Thus, he took a job as an advertising representative for the Seiberling Rubber Company, which required him to travel extensively through the southern states as he assisted Seiberling tire dealers and sought out interesting short line railroads.

"In the summer of 1941, Bob and a friend came to Colorado for the first time, making an unforgettable circle tour on the narrow gauge. Bob become completely enamored of the slim gauge railroads of Colorado. After military service with the Army Signal Corps during WWII in Iran, where he studied the Persian railroads and learned to read Farsi, Bob returned to his job with Seiberling, but the lure of Colorado remained strong. He made repeated vacation trips to narrow gauge country in 1945, 1946 and 1947, eventually deciding to make his home here. In 1948 he quit his job, and he and a friend from Ohio pooled their resources to open the Narrow Gauge Motel in Alamosa. The motel grounds offered a fine place to display some of the narrow gauge equipment he had purchased, along with that saved by the Rocky Mountain Railroad Club. While at the motel, he began the sporadic publication of a very significant newsletter called simply “Narrow Gauge News” which later became the Colorado Railroad Museum’s “Iron Horse News.” At Alamosa, Bob Richardson tirelessly railed against the abandonment of the historic narrow gauge lines. It can accurately be said that his untiring efforts and the publicity he generated were among the primary reasons that the Silverton Train and the Cumbres and Toltec were preserved for future generations to savor," wrote upon Richardson's death.

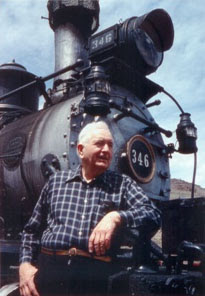

"While in Alamosa, Bob amassed a formidable collection of railroad artifacts and equipment, including famed D&RGW locomotive No. 346, which he purchased with his own funds in 1950. Then Cornelius W. Hauck, another prominent railroad enthusiast from Ohio, acquired D&RGW 318 and placed it at the motel. Bob’s friendship with “Corny” Hauck led to the establishment of the Colorado Railroad Museum in Golden, which is today recognized as one of the truly great railroad museums in the country. Purchase of the former farm just east of Golden was completed in 1958, and the museum was officially opened to the public in July of 1959. Construction of the Iron Horse Motel next door was intended to be an additional source of operating revenue but instead proved to be overly time-consuming and was sold. Several years down the road, the motel was purchased and razed to make way for the roundhouse restoration facility and to enable completion of a loop of narrow gauge track. The Robert W. Richardson Railroad Library at the museum was created and named in his honor. Bob served as the distinguished Executive Director of the Colorado Railroad Museum until 1991 when he made the decision to retire and move back to Pennsylvania in that part of the country where he had been raised and where his nephews and niece reside. Even in retirement he continued to produce significant volumes dealing with railroad history, especially here in Colorado. Today, persons treasure their friendships and even casual meetings with him and will long remember his myriad contributions to Colorado railroad history. It is no exaggeration to say that he did more than any other person to preserve Colorado’s unique railroad heritage. We are indeed fortunate that his photographs and writings will be available for future generations of railroad enthusiasts and historians," says Ron Hill in tribute.