"Your stakes are a little far apart"

By Rob Carrigan, robcarrigan1@gmail.comIt was not the first time that the way a law was written — made someone a fortune.

"The Union and Sherman mines were good producers of silver and other metals in 1876 and in July of that year, prospector J.B. Ingram grew curious about them. They seemed farther apart on the mountainside than they should be, and sure enough, by measurement he found several hundred feet not legally included in either. So shortly he had a claim, a mine, a fortune," wrote Lambert Florin in his 1970 expansive roundup of "Ghost Towns of the West."

"During August 1875, John Fallon and a partner were the first prospectors to find what would be called the Smuggler Vein in Marshall Basin. They staked their adjoining Sheridan and Union claims on the rich upper section of the vein just below the 12,000 ft. elevation line. At the time, the only way into Marshall Basin was a bushwhack trail that crossed through the “Keyhole” to the Ouray side of the mountains," according to the Mining History Association, in a paper presented at Annual Conference June 9-12, 2016, Telluride, Colorado on Mining History of Telluride, Colorado.

"This remote setting, however, did not hinder a three man party led by J. B. Ingram from reaching Marshall Basin the following summer. Apparently, these men entered the basin ahead of Fallon and his partner, and were canny enough to recognize that their predecessors had staked more ground than was allowed by current mining law. As a result, the interlopers staked a new claim called the “Smuggler” that incorporated a lower parcel from the Sheridan claim with an upper parcel from the Union claim. As luck would have it, the Smuggler proved to be located on the widest, richest, and deepest part of the vein."

Altogether, these three discoveries and the rush that followed led to the establishment of the Upper San Miguel Mining District. Hundreds of mining claims covered the rugged topography. A camp called Newport was established at the east end of the Telluride Valley. This end of the valley was also where a succession of mills was erected over time, says the Mining History Association.

"In 1877, the town of San Miguel was platted further west in the Telluride Valley, but a year later, a new community named Columbia was incorporated a mile closer to the mines. Due to this superior location, it became the dominant town. Eight years later though, the US Post Office asked Columbia to change its name. The reason given was that there was a Columbia, California, and too much mail was being misdirected between the two communities because poor penmanship used to write the initials CALA for California or COLO for Colorado was often too hard to decipher."

Since Columbia, Colorado, was a newer town, it had to choose a new name. By chance, a large hunk of gold ore misidentified as a telluride form of sylvanite had recently been found at the Sheridan Mine. This led to renaming the town “Telluride” because telluride gold ore was considered to be very rich and the catchy name might attract mining investors. Ironically, the element tellurium is practically non-existent in the entire San Juan Mountains, says the Mining History Association.

"Between the years 1887-1889, consolidation of the mines along the great Smuggler Vein in Marshall Basin led to the formation of the Smuggler-Union Mining Company. Seven years later in 1896, the wealthy Rothschild family from Europe organized the Tomboy Gold Mines Company in neighboring Savage Basin. Altogether, these two mining companies were the best producers in the Upper San Miguel Mining District until they closed in the late 1920s."

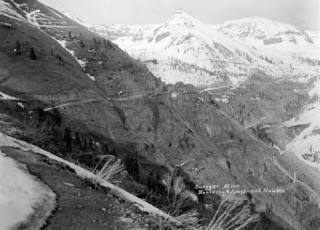

The Smuggler-Union mine used to be located along Tomboy Road high above Pandora (east of Telluride). It was an startling complex consisting of a multistory boarding complex housing hundreds of miners and was perched precariously close to the edge.

A forerunner to the ski tram towers that would later dot the nearby mountains, an elaborate tram system carried ore down to Pandora, and remnants of steam boilers, chain, tram cable, and rusted piping are still scattered in the area. The "Bullion" Tunnel was drilled as a crosscut underneath the mine in an effort to reduce operating costs.

In November of 1901, 22 men were killed as a result of a fire in the mine. A hay fire broken out near the mine portal. The draft sucked the smoke in and many miners died of smoke inhalation. But it could have been much worse, as nearly 200 men were working there that day according to a dispatch in the Salida Mountain Mail, at the time.

Impressive Hydroelectric Powerplant

The Smuggler-Union Hydroelectric Powerplant was built to power the Smuggler-Union Mine 2,000 feet below the mine in 1907, providing alternating current for industrial purposes. The plant was proposed by Smuggler-Union Mine manager Buckley Wells who live in the residence as a summer home until the 1920s. It was originally accessed in winter by an aerial tramway but that was eventually destroyed. It operated in its original configuration until its decommissioning in 1953, serving the Idarado Mining Company.

The living quarters and especially the power house/generator fell into disrepair and were heavily vandalized by the time of the historic registry survey in 1979. A local resident, Eric Jacobson, acquired a 99-year lease from the Idarado Mining Company for the property in 1988 and proceeded to restore the facility and eventually moved his family into the residence. The AC plant was restored to operation in 1991 with power being generated by its original 2300 volt Westinghouse Electric AC generator, one of the oldest AC generators still in operation. In 2010 Jacobson gave up the lease to the Idarado Mining Company citing continual regulation and legal problems associated with the site. Idarado has kept the plant in operation and the power generated now provides about 25 percent of Telluride's demand for electricity. As of 2012, the plant generated approximately 2,000 megawatt hours a year – enough electricity to power about 2,000 average American homes, which is purchased from Idarado by the local San Miguel Power Association. The Smuggler-Union Powerplant was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on December 27, 1979.

Photo Information:

1. Smuggler-Union Mine about 1910. Photo Joseph E. Byers.

2. Smuggler-Union mine, mill, and boarding house in Savage Basin. Walker Art Studios. About 1935.

3. Smuggler-Union Hydroelectric Powerplant, at Bridal Veil Falls, southeast of Telluride.