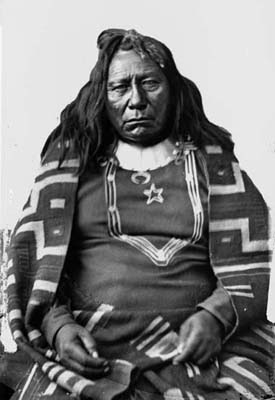

Sometimes, it can be very hard to live up to an image. Tastes and distastes contribute to a man's reputation. Ute ‘Chief’ Colorow wasn't bashful about letting his be known. Among other things, the large man made a reputation for himself for his legendary fondness of biscuits and syrup – along with his intense dislike for what he considered encroachment on his native land.

According to the Aspen History Society, “Colorow was one of several leaders of a small, unsophisticated splinter group of Utes in Northwestern Colorado, called the White River Band.

In the spring of 1879, Colorow's followers were pressured by local Indian agent, Nathan Cook Meeker, to plant a field of garden crops in a field they had traditionally used to graze their horses.”

Meeker’s miscalculation made members of the band mad.

“In anger, one of the Utes confronted Meeker and ultimately threw him to the ground. Meeker overreacted and sent telegrams to Gov. Pitkin, 200 miles away in Denver, requesting troops be sent for his protection. The army, lulled by general peace on the frontier, and anxious to give its men some "field experience," sent two companies of cavalry and one mounted infantry, (about 200 men) from Wyoming's Fort Rawlins with specific instructions that the Utes not be molested,” says material from Aspen History Society.

“The Utes, however, clearly remembering the massacre at Sand Creek 15 years earlier, panicked. Many moved to new camps or fled the area. But, in the ensuing confusion, a shot was fired beginning events, which would end in the grizzly death of Meeker and all other agency employees. In addition, 2 women, including Meeker's wife, and 2 children were abducted by the Utes.

Colorow explained at the investigation into these events that the stake driven through Meeker's mouth had been necessary "to stop his infernal lying on his way to the spirit world.”

After what became known as the Meeker Massacre in 1879, the Utes were sent to the Uintah Indian Reservation on the Colorado-Utah border.

“Colorow was one of the last to leave and promised, ‘I go now. In winter I come back - hunt deer and elk.’ Every winter for seven years he returned to his Shining Mountains for the traditional winter hunt. Eventually the white men grew too numerous. Colorow and his men retired to the red rocks and made almost daily rounds of the settlers demanding food, clothing and anything else to which they took a fancy. One particularly notable fancy was biscuits, thick with syrup, which Colorow would eat as fast and as long as a ranch wife could bake them,” according a Ken-Caryl Ranch history.

In a reminiscence written for the State Historical Society, Dora I. Foster tells of visiting her aunt in Bradford City and of the day the Indians appeared. Dora and her aunt made biscuits as fast as they were able, but since they did not want the Indians to find their store of flour in the pantry, brought out only enough at one time for a batch or two. Finally the aunt, tiring of the game, told the Indians she had no more flour. The Indians, thereupon, brought forth more flour wrapped in greasy skin pouches and bits of dirty rags. The baking continued.”

Other stories cropped up of his legendary love for biscuits in the Florissant and Ute Pass areas.

“He himself was quarry for the government men, but he eluded them until 1888 when he was wounded in a battle with a posse. He went into hiding at his camp at the mouth of the White River near the Uintah Reservation, but developed pneumonia and died in December. A cave north of Ken-Caryl was one of his favorite places and it is still called by his name,” notes the Ken-Caryl Ranch history.

“Colorow’s Cave” was a longtime gathering place for others as well.

In 1962, an article in the Littleton Independent, by Houstoun Waring, editor at the time, talks about the sale and plans for the cave.

“The giant Colorow Cave, eight miles west of the Centennial Race Track (at Littleton) may soon be converted into a church or some other use. It is proposed to place a plastic roof over the upper portions, as there is a gap of several yards in the ‘ceiling.’ The ‘cave’ is a space between uptilted rocks so characteristic of the region south of Morrison, Colo.,’ Waring wrote in the March 30, 1962 edition of the Independent.

“The property belongs to L.D. Bax , who plans to close a deal selling 350 acres. About 200 select homes will be built there, according to one of the developers. The cave, according to legend, was used by Ute chief Colorow. Early settlers report the place provided shelter for the Indians. It probably contains 2,000 to 3,000 square feet of floor, and it resembles a large room with high vaulted ceiling. Hundreds of picnic fires have been built there. As the floor is level, it provided a good place for meeting — after tables and seats had been added.

“Maurice Frink, Director of the State Historical Society, has some unsigned documents concerning the cave. According to these, Major (R.B.) Bradford, who was born near Nashville in 1813, came to Colorado in 1859 with a letter of credit from Russell, Majors & Waddell of Pony Express fame. Cattle belonging to his firm grazed on the surrounding slopes. Legend has it that Major Bradford brought with him three slaves, and that their remains lie in rocky graves there,”

The first westbound stage stop out of Denver was reportedly on this ranch and travelers stopped for the night there before going up Sawmill Gulch. A little town called Piedmont is said to have been located on the land. Bradford’s purchases in this area began in 1860, with W.H. Middaugh as a partner.

Today, Colorow's Cave is part of Willowbrook and is also known as the Willowbrook Amphitheatre.

###