She always vanished the moment someone on

the train recognized and called her by name

By Rob Carrigan, robcarrigan1@gmail.com

The first time I heard the

story of Emma Mentzer was in Brian Tobin’s history class, as a junior in high

school. In between his rants about “screaming Arab regulars,” Tobin was famous

for dramatic accounts of seemingly minor details in life and times of eras

past. They provided texture and color for history that I have enjoyed to this

day. He told personal stories of

fishing with hand grenades as a U.S. Marine in Viet Nam, (toss a grenade in the

lagoon, jump back, then gather the fish) and strange and terrible tales of fear

and loathing in the heart of American depravity.

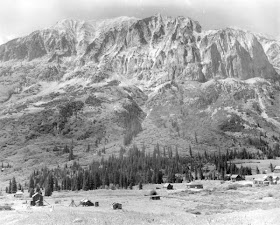

But the yarn of Emma’s

plight carried special meaning because it was right up the railroad there in

Telluride – if only the railroad was still around.

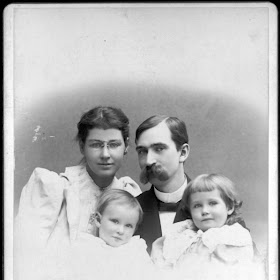

By all accounts, there was

no questioning that Emma Mentzer was a fine-looking woman. Variously described

as “a handsome woman and very devoted to her husband,” and “pretty woman from

Chicago who, by everyone’s estimation had married well when she wed a young

physician named O.F. Mentzer,” her story has captured yarn weavers attention

for more than a hundred years.

Trouble is, figuring out

what is her story.

Swirling around in the snow

and thin air up there are several fantastic versions and separating the gold

from the overburden is an arduous task.

The various versions twist and turn different ways, even to point of

indentifying who she was, and what was her name. Was it Emma, or “Essie?” Was

she patron of Chicago society, or former Madam at a house of ill repute? All

are questions that have been pondered for a century now, hairs that have been

split and examined, but without definitive answer. I’m not sure I am up for

answering them either. So, I will tell you what I know.

Oscar F. Mentzer traveled

from his native Sweden to the United States in 1881 and by 1890, he had set up

a physician’s practice on Larimer Street in Denver.

“He enjoyed a reputation as

a skilled surgeon and built up a large practice worth reportedly $15,000 per

year,” according to Carol Turner, in her book “Notorious Telluride: Wicked

Tales from San Miguel County.”

“Mentzer was also known as a

charitable, kind doctor who treated many poor patients without charge.”

Oscar and Emma (formerly Monroe)

had met when they were both guests at the Hotel Albert in Denver and were married

in Colorado Springs in July of 1894.

“Unfortunately, despite his

happy circumstances, thirty-year-old Dr. Mentzer was and alcoholic,” writes

Turner. “His drinking soon began to interfere with his practice. He missed days

in the office and patients left his care, seeking a more sober physician. Emma

Mentzer left her husband and returned to Chicago, where she reportedly divorced

him.”

According to Turner’s

account, the good doctor announced to his friends that he was getting away from

the temptations of the city and moving to Telluride to reform and set up a new

practice.

He did so, and after a year

in the roaring camp, as Turner describes, he was generally respected around the

camp as a “very able surgeon.”

“However there were ‘some

incidents where he committed acts that did not meet with the general approval…

and he was feared to a certain extent, especially by female patients.’”

In late 1897, Oscar renewed

contact with his ex-wife. Reports in the Telluride papers said that she told

him that she was “sick and starving and imposed upon and if she didn’t have

him, she would have to starve to death.”

The doctor began sending

money to his former wife in Chicago and continued throughout 1898, accounting

for more $900 that year (which was a tidy sum in those days, equating to

substantial annual salary) as revealed in records later. All this time, he

begged his wife to return and promised his complete reform. In July, she

apparently agreed to meet him in Denver and they renewed their marriage, and

returned to Telluride in early August.

On the condition that he

stay sober apparently, but that was not to be.

Oscar’s former partner,

pharmacist S.A. Gross told the Telluride Journal later, “Mentzer was here six

weeks or so ago. He wanted to come back with me again but I told him no. He was

too far gone. He looked seedy from drinking so much. He said he was going to

stop drinking for good, but I could see that he never again would be the man he

had been, so I wouldn’t have him.”

Upon the Mentzer’s return to

Telluride, Emma’s brother Will Monroe and his wife, also moved to the camp with

intentions of going to work at the Bessie Mill as engineer. They stayed with

the Mentzers.

“During the first week in

October, Mentzer visited Tompkins Hardware Company in Telluride and purchased a

.32 caliber Iver Johnson pistol. He told the salesman he needed protection

against “dogs and holdups” when he traveled at night to places like Sawpit. The

salesman insisted that Doc Mentzer was perfectly sober when he purchased the

weapon or he would not have sold it to him,” says Turner.

Will Munroe, Emma’s brother,

told the following account of the night of Oct. 7, in testimony before the

court, during Oscar Mentzer’s trial for the murder of Emma Mentzer.

The Monroes and Mentzer’s

had a pleasant evening together and the Doctor was jovial and smiling. About

9:30 in the evening, Emma suddenly called to her brother from another room.

Arriving right away, he heard a scream and a shot. As he entered the room, the

doctor turned to him, smoking gun in hand. The two wrestled for control of the

pistol and Will Munroe was able to remove the gun and toss it to his wife who

had arrived according to his testimony. She in turn, threw it out in the yard.

The two men “both splendid specimens of physical manhood” continued the fray

until Will Monroe got the upper hand and knocked the doctor unconscious. He

then reportedly dragged him out to the porch and threw him in heap.

Only then did he return to

the house and discover his sister had been shot in the temple. Emma died from

her wound about half hour later, according to what Will told police. When they

arrived, the doctor was still unconscious in a heap on the porch. He remained

so even after they carted him off to the sheriff’s office as was deposited on a

cot there.

The next issue, the San

Miguel Examiner lamented over the death of Emma Mentzer.

“Mrs. Mentzer was a most

charming and amiable woman and possessed the traits that made her lovable to

all, and her sad fate brings great sorrow to her relatives and the community

alike.”

Meanwhile, it became obvious

to the authorities finally that the Doctor was suffering from a serious head

injury. The two doctors called, Hall and Clark, were unable to revive the man

and determined that they must trepan his skull, or drill a hole to relieve

pressure on the brain. The procedure seemed to have worked as the doctor, with

additional help from another inmate, pulled through.

“Three weeks after the

shooting, Mentzer had his preliminary hearing,” writes Carol Turner. “The only

witnesses, Will Monroe and his wife, gave mixed and contradictory testimony

during the hearing, and observers began to express doubts about their

reliability and respectability.”

There was rampant

speculation that these witnesses, may in fact, hustle out of town in the middle

of the night.

In the doctor’s version of

the story, he had no intention of shooting his wife and the gun went off

accidently in the struggle with Monroe.

The verdict was delivered to

a packed courtroom early in the day on December 5, 1898 finding Oscar Mentzer

guilty of second-degree murder, with a recommendation for leniency. He was

sentenced to 20 years.

According to Turner, “After

the trial, public opinion swung sharply in Mentzer’s favor when detail emerged

about the questionable character of the Monroes, including Emma.

(The same day the jury

reached a verdict,) Will Monroe’s real wife arrived in town, having traveled

all the way from Illinois. It turned out she and her attorneys had been

scouring the country looking for Monroe, and the headlines about the shooting

had revealed his whereabouts.”

“Mrs. Monroe said her

husband had beaten her and strangled her on many occasions. Finally he took her

and the children to her sister’s house in Chicago and left them there. After

many weeks without word, she hired detectives to hunt them down. They found

them in a Chicago bordello with the woman he now claimed was his wife. She

stated further that Emma Mentzer was the “landlady” of the Chicago bordello,

and at that time was in court facing charges of theft. The Monroes took off and

that was the last she knew of them until she read in the papers of the shooting

in Telluride.

According to the Telluride

Journal at the time:

“The whole history of her (Mrs.

Monroe’s) life with Monroe show him to be a most despicable character, and it

is a little remarkable that the proven bigamists and self confessed perjurer

should be allowed to quietly slip away without punishment. His sister, whose

evil influence had much to do with his downfall and outrageous treatment of his

wife and children, and their final abandonment, is in her grave, sent there by

a bullet fired by the man she had driven into a frenzy.”

By that time, Will Munroe

and his “other wife” had disappeared from Telluride. There was talk of a new

trial but Oscar Mentzer had already began serving his time in Canon City.

His medical training

apparently had a role in securing a spot in the prison dispensary. Injuries

sustained from the beating from Monroe made it difficult to sleep and he took

chloral hydrate to help. Twenty months into his sentence, with his friends and

attorney working on a possible pardon, he appeared at the prison kitchen asking

for coffee but before he could take a sip, he fell to the floor and died, cause

attributed to an overdose of chloral hydrate. He was 36.

But here is where some

versions of the story take on a life of their own.

Tales of “Essie” (instead of

Emma) Mentzer being sighted on the Rio Grande Southern railroad became a

standard. In most such yarns, the Doctor was a Jekyll an Hyde sort of fellow

with not only binge drinking problem but a maniacal drug habit as well. According

to the stories, in front of many witnesses, a beautiful woman would appear as

real as you or I. People on the train would offer her sympathy and help, but

she was inconsolable and frantic, hysterically repeating, “He’s almost here. I

have to go.” Then disappear into the thin mountain air, right in front of

everybody.

In one version of the story

by Dan Asfar appearing in his book, Ghost Stories of Colorado, “with every

successive mile, she grew more anxious, feeling the presence of her homicidal

husband get stronger and stronger. She always vanished the moment someone on

the train recognized and called her by name. If that didn’t happen before she

was 10 miles out of town, she would just vanish on her own, unable to deal with

the dread of an unseen husband’s approach any longer. Those 10 miles were as

far out of Telluride as Essie Mentzer was ever able to get.”

One question from me only, “Do

we call the ghost Essie, or Emma?”

I suppose we should inquire

as well, if she ever went fishing with hand grenades?

###