The spectators got their thrill, but it cost Johnstone his life

By Rob Carrigan, robcarrigan1@gmail.com

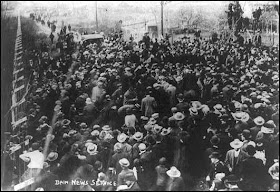

A hundred years ago — to most folks — flying in an airplane seemed to be just taking one step toward death’s door. The presumption was reinforced at Overland Park in Denver one November afternoon in 1910, as thousands of air show spectators watched Ralph Johnstone plummet to his death in front of them.

“He had gambled with death once too often, but he played the game to the end, fighting coolly and grimly to the last second to regain control of his broken machine. Fresh from his triumphs at Belmont Park, where he had broken the world’s record for altitude with a flight of 9,714 feet, Johnstone attempted to give the thousands of spectators an extra thrill with is most daring feat, the spiral glide, which had made the Wright aviators famous. The spectators got their thrill, but it cost Johnstone his life,” according to newspaper accounts at the time.

It was actually Johnstone’s second flight that fateful day. He had gone through a series of dips, rolls and glides without incident with others of the Wright Brothers trained flying crew. The former Vaudeville bicycle stunt performer took the biplane up once more and out toward the foothills to gain altitude.

“Still ascending, he swept back in a big circle, and as he reached the north end of the enclosure, he started his spiral glide. He was then at an altitude of about 800 feet. With his plane tilted at an angle of almost 90 degrees, he swooped down in a narrow circle, the aeroplane seeming to turn almost in its own length. As he started the second circle, the middle spur, which braces the left side of the lower plane, gave way, and the wing tips of both upper and lower planes folded up as though they had been hinged. For a second, Johnstone attempted to right the plane by warping the other wing up. Then the horrified spectators saw the plane swerve like a wounded bird and plunged straight toward the earth,” said a report appearing in the Savannah Tribune at the time.

Ever a cool one, the young aviator didn’t panic however.

“Johnstone was thrown from his seat as the nose of the plane swung downward. He caught on one of the wire stays between the airplane and grasped one of the wooden braces of the upper plane with both hands. Then, working with hands and feet, he fought by main strength to warp the planes so that their surfaces might catch the air and check his descent. For a second it seemed that he might succeed, for the football helmet the wore blew off and fell much more rapidly than the plane.”

About 300 feet from the ground the plane turned end-over-end then plunged, scattering fleeing spectators.

“Scarcely had Johnstone hit the ground before morbid men and women swarmed over the wreckage, fighting with each other for souvenirs. One of the broken wooden stays had gone almost through Johnstone’s body. Before doctors or police could reach the scene, one mad had torn this splinter from the body and run away, carrying his trophy with the aviators blood still dripping from its ends. The crowd tore away the canvass from over the body, and even fought for the gloves that had protected Johnstone’s hands from the cold,” said the Savannah paper.

When Ralph Johnstone died his widow was quoted in the Kansas City Times, "I never was worried about Ralph. He was so brave and careful. It seemed nothing could happen to him. I did not take into consideration a mishap to his machine."

Just three days before his final flight Johnstone was quoted one last time. "It's going to get me some day. It's sooner or later going to get us all. Don't think our Aim is the advancement of science. That is secondary and is worked out by the men on the ground. When you get into the air, you get the intoxication of flying. No man can help feeling it. Then he begins to flirt with it, tilt his plane into all sorts of dangerous angles, dips and circles. This feeling is only the trap it sets for us... the non-mankilling airplane of the future will be created from our crushed bodies."

A year later, reports in the New York Times noted that his wife had decided to take up flying herself.

“Widow of Man Who Was Dashed to Death to Try for License,” said the the Sept. 14, 1911, headline in the Times.

“Although leading aviation schools have steadfastly refused to teach feminine pupils at any price, women are gradually forcing their way into the hazardous game, and followers of the sport are discussing with interest today the report that Mrs. Ralph Johnstone of Kansas City, whose husband was killed at Denver, is soon coming to New York to master the craft that widowed her. It is understood that she will take lessons at the aviation colony on Long Island with a view to becoming a licensed professional aviator. There are only two licensed women aviators in this country at present-- Miss Mathilde Moisant and Miss Harriet Quimby---both of whom are now on Long Island,” reported the Times.

###

No comments:

Post a Comment